Deep BrainWatch

Deep learning for non-invasive intracranial pressure monitoring

Highlights

Clinicians at Vall d'Hebron Barcelona Hospital needed a safe, scalable method to monitor intracranial pressure in patients with neurological conditions, as the current invasive approach requires drilling into the skull and carries risks of infection and hemorrhage.

Develop a non-invasive, machine learning-based solution to estimate ICP from cerebral blood flow signals acquired using near-infrared photonic sensors.

Designed and validated a wavelet-based deep learning model (mWDN), benchmarking it against 9 time-series models and deploying an ensemble strategy with rigorous preprocessing and cross-validation.

Achieved 71% of predictions within ±6 mmHg in the clinically critical 0–15 mmHg range, enabling accurate, bedside-compatible ICP tracking without surgical intervention.

Core Team

Overview

Intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring is vital in diagnosing conditions such as traumatic brain injury and hydrocephalus, but the current gold standard is invasive and risky. This project leverages biophotonics and machine learning to provide an accurate, non-invasive alternative.

We used cerebral blood flow (CBF) measurements acquired via diffuse correlation spectroscopy (DCS) and developed a deep learning pipeline to predict ICP from these signals. After benchmarking 10 state-of-the-art architectures, a wavelet-based model (mWDN) was selected and further enhanced via ensemble techniques. This work was validated on one of the largest existing datasets of patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH), totaling over 200 hours of data across 44 patients.

Data

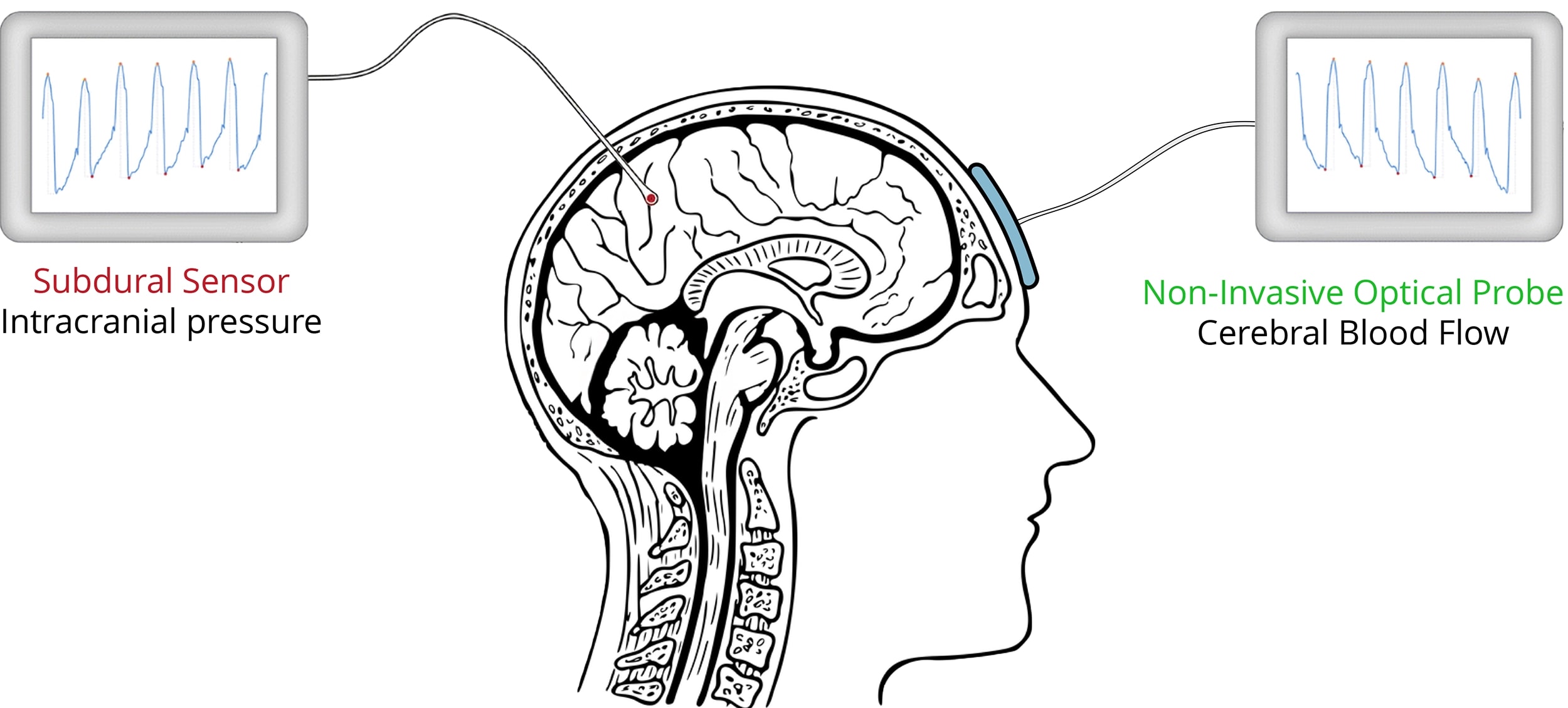

This study utilized synchronized, high-resolution recordings of CBF and ground-truth ICP from 44 patients diagnosed with iNPH at Vall d'Hebron University Hospital. The CBF signals were measured non-invasively using a near-infrared DCS probe placed on the frontal lobes, while ICP ground truth was recorded via an invasive subdural catheter (Figure 1).

- •CBF Source: DCS optical probe (785 nm, frontal lobes, 40 Hz)

- •ICP Source: Invasive subdural sensors (Raumedic Neurodur-P)

- •Preprocessing: Signal normalization, artifact filtering, statistical outlier removal (Tukey fence, Kolmogorov–Smirnov distance)

- •Time Windowing: 600-sample segments (~15-second windows)

- •Dataset Size: 22 subjects (90 hours) for training/validation, 22 subjects (110 hours) for testing

The test set reflects real-world deployment conditions with no data leakage, ensuring robust generalization.

Methods

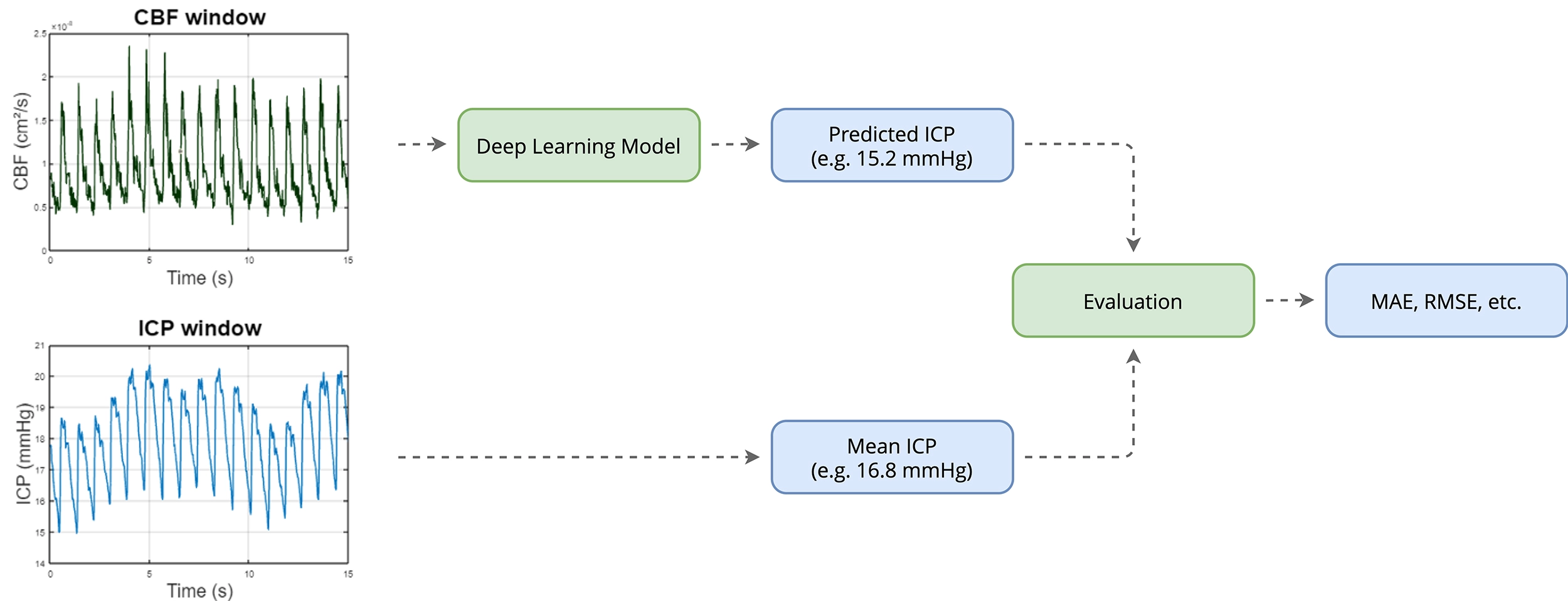

The proposed approach frames ICP prediction as a supervised regression problem using short segments of CBF signals as input (Figure 2). The primary model used was the multilevel Wavelet Decomposition Network (mWDN), selected for its ability to capture multi-resolution temporal dynamics inherent in pulsatile CBF signals.

- Model Benchmarking: mWDN was compared against 9 state-of-the-art architectures including ResCNN, InceptionTime, XceptionTime, LSTM-FCN, GRU-FCN, TST, TCN, MultiRocket, and XCM.

- Sliding Window Modeling: Each 600-sample CBF window (15 seconds) is mapped to the corresponding mean ICP value over the same interval.

- Loss Tuning: Models were trained using multiple loss functions (MAE, MSE, Huber, and Log-Cosh) to assess robustness to outliers and physiological variability.

- Cross-Validation: A two-level scheme was used – 5-fold intra-subject validation and inter-subject hold-out evaluation – to prevent data leakage and test generalization.

- Ensembling: Top-performing models (mWDN, InceptionTime, and XCM) were combined to enhance stability and reduce variance.

Results

The proposed model demonstrated robust performance in predicting ICP across clinically meaningful ranges:

- Validation MAE: 2.6 mmHg – aligning with international clinical accuracy standards.

- Test MAE: 5.8 mmHg on unseen subjects.

- Test RMSE: 6.7 mmHg.

- Ensemble Performance: MAE of 4.4 mmHg, RMSE of 5.7 mmHg.

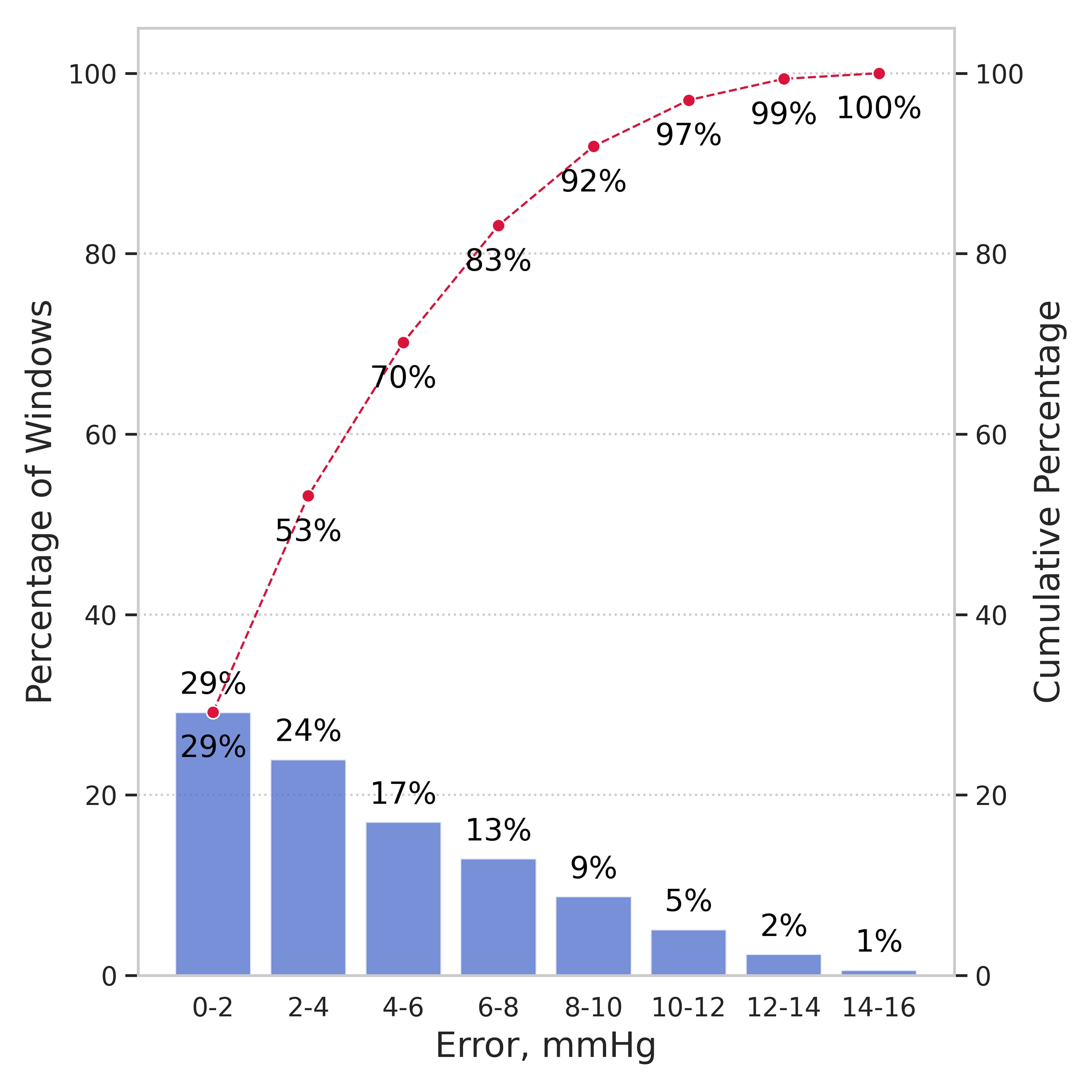

- Clinical Accuracy: 70% of predictions within ±6 mmHg in the 0–15 mmHg range.

- ROC Analysis: AUC ≈ 0.82, indicating high discriminative power.

According to standards set by the American National Standards Institute and the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, non-invasive ICP monitoring must achieve:

- •±2 mmHg accuracy for true ICP values in the 0–20 mmHg range

- •±10% accuracy for ICP values above 20 mmHg

While the test MAE exceeds the strict ±2 mmHg threshold, the model remains clinically actionable in the most relevant range for iNPH patients: 0–15 mmHg. The error distribution (Figure 3) confirms that predictions cluster within acceptable bounds.

To visualize model behavior, Figure 4 shows predictions on validation subjects, where red-shaded regions denote validation windows. The predicted ICP (blue) closely tracks the true ICP (green), capturing both slow drifts and fast spikes. Figure 5 presents performance on completely unseen test subjects, demonstrating strong generalization.

Conclusion

This work presents a clinically viable, non-invasive method for ICP estimation using deep learning on CBF signals acquired via diffuse correlation spectroscopy. By training a wavelet-based neural network on synchronized invasive and non-invasive recordings from 44 iNPH patients at Vall d'Hebron University Hospital, we demonstrated that ICP can be accurately predicted from CBF dynamics without the need for surgical monitoring.

The model achieved a mean absolute error of 2.6 mmHg on validation data, aligning with the ±2 mmHg accuracy target. On a held-out test set, performance remained robust (MAE: 5.8 mmHg), with 70% of predictions within ±6 mmHg in the 0–15 mmHg interval, where clinical intervention is often most critical.